THE LEGACY OF MUSLIM RULE IN INDIA by K.S. LAL

Peter Klevius additional title: Monotheist evil against polytheism and Atheism

Read how two craniopagus twins born 2006 solved the "greatest mystery in science" - and proved Peter Klevius theory från 1992-94 100% correct.

Table Of Contents

1. Preface

2. Abbreviations used in references.

3. The Medieval Age

4. Historio graph y of Medieval India

5. Muslims Invade India

6. Muslim Rule in India

7. Upper Classes and Luxurious Life

8. Middle Classes and Protest Movements

9. Lower Classes and Unmitigated Exploitation

10. The Legac y of Muslim Rule in India

11. Bibliography

Preface

Had India been completely converted to Muhammadanism during the

thousand years of Muslim conquest and rule, its people would have taken

pride in the victories and achievements of Islam and even organised

panislamic movements and Islamic revolutions. Conversely, had India

possessed the determination of countries like France and Spain to repulse

the Muslims for good, its people would have forgotten about Islam and its

rule. But while India could not be completely conquered or Islamized, the

Hindus did not lose their ancient religious and cultural moorings. In short,

while Muslims with all their armed might proved to be great conquerors,

rulers and proselytizers, Indians or Hindus, with all their weaknesses,

proved to be great survivors. India never became an Islamic country. Its

ethos remained Hindu while Muslims also continued to live here retaining

their distinctive religious and social system. It is against this background

that an assessment of the legacy of Muslim rule in India has been

attempted.

Source-materials on such a vast area of study are varied and scattered.

What we possess is a series of glimpses furnished by Persian chroniclers,

foreign visitors and indigenous writers who noted what appeared to them of

interest. It is not an easy task, on the basis of these sources, to reconstruct

an integrated picture of the medieval scenario spanning almost a

millennium, beginning with the establishment of Muslim rule. The task

becomes more difficult when the scenario converges on the modem age

with its pre- and post-Partition politics and slogans of the two-nation theory,

secularism, national integration and minority rights. Consequently, some

generalisations, repetitions and reiterations have inevitably crept into what

is otherwise a work of historical research. For this the author craves the

indulgence of the reader.

10 January 1992

K. L. Lai

The Medieval Age

Chapter 1

If royalty did not exist, the storm of strife would never subside, nor selfish

ambition disappear'

- Abul Fazl

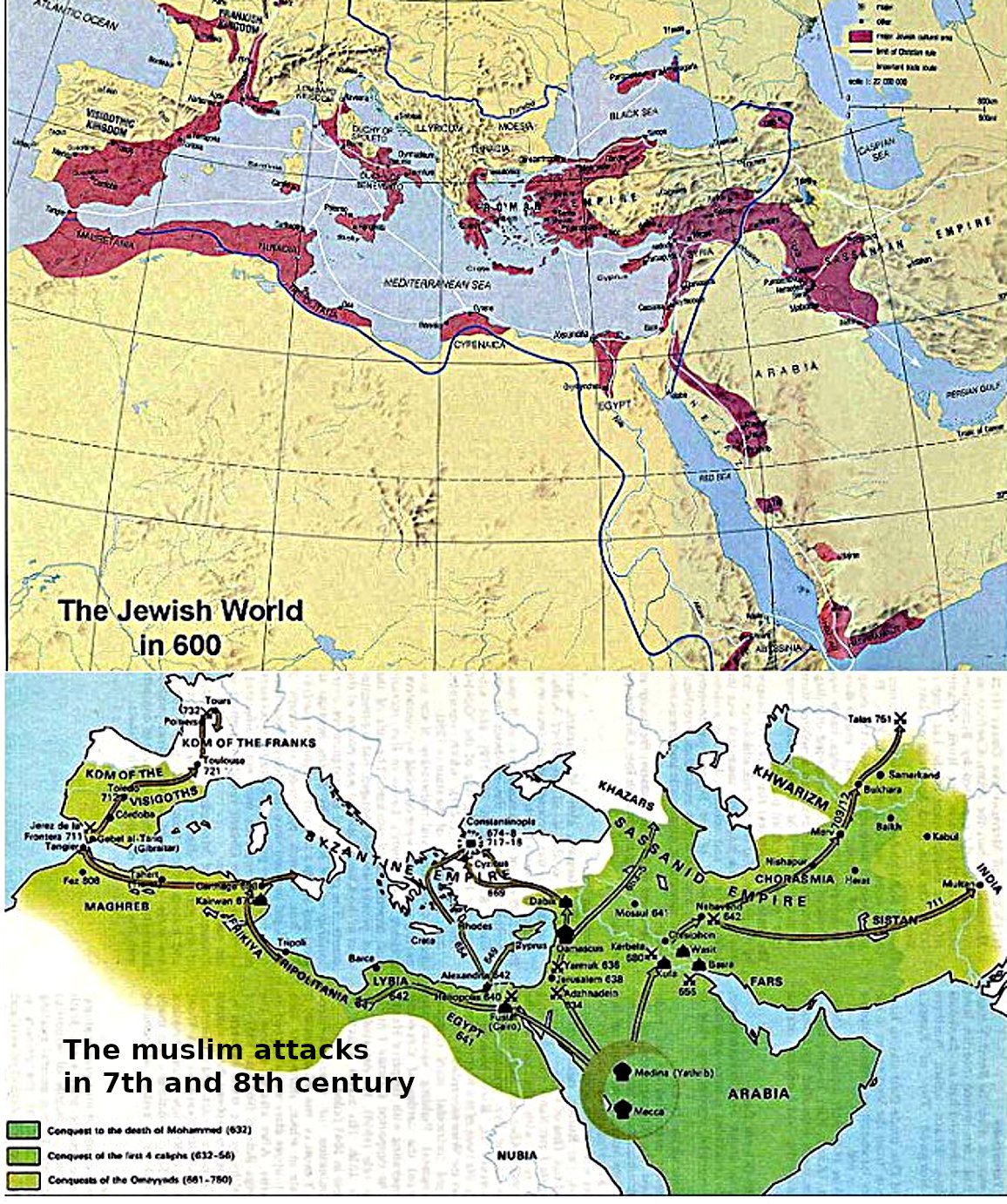

Muslim rule in India coincides with what is known as the Middle Ages in

Europe. The term Middle Ages or the Medieval Age is applied loosely to

that period in history which lies between the ancient and modern

civilizations. In Europe the period is supposed to have begun in the fifth

century when the Western Roman Empire fell and ended in the fifteenth

century with the emanation of Renaissance in Italy, Reformation in

Germany, the discovery of America by Columbus, the invention of Printing

Press by Guttenberg, and the taking of Constantinople by the Turks from

the Byzantine (or the Eastern Roman) Empire. In brief the period of Middle

Ages extends from C.E. 600 to 1500.

Curiously enough the Middle Age in Europe synchronises exactly with

what we call the medieval period in Indian history. The seventh century saw

the end of the last great Hindu kingdom of Harshvardhana, the rise of Islam

in Arabia and its introduction into India. In C. 1500 the Mughal conqueror

Babur started mounting his campaigns. And since these foreign Muslim

invaders and rulers had come not only to acquire dominions and extend

territories, but also to spread the religion of Islam, war and religion became

the two main currents of medieval Indian Muslim history.

Kingship

War is the work of kings turned conquerors or conquerors turned kings.

Therefore it was necessary for the medieval monarch to be autocratic,

religious minded and one who could conquer, rule and subserve the interest

of religion. Such was the idea about the king in medieval times, both in the

West and the East.

The beginnings of the institution of kingship are obscure. Anatole France

attempts to trace it in his Penguin Island, a readable satire on (British)

history and society. That is more or less what he writes: Early in the

beginning of civilization, the peoples primary concern was provision of

security against depredations of robbers and ravages of wild animals. So

they assembled at a place to find a remedy to this problem. They put their

heads together and arrived at a consensus. They will raise a team of security

guards who will work under the command of a superior. These will be paid

from contributions made by the people. As the assembled were still

deliberating on the issue, a strong, well-built young man stood up. He

declared he would collect the said contributions (later called taxes), and in

return provide security. Noticing his physical prowess and threatening

demeanour they all nodded their assent. Nobody dared protest. And so the

king was born.

In whatever manner and at whatever time the king was born, he was, in

the Middle Ages, personally a strong warrior, adept at horsemanship, often

without a peer in strength. He gathered a strong army, collected taxes and

contributions and was surrounded by fawning counsellors. They bestowed

upon him attributes of divinity, upon his subjects those of devilry, thus

making his presence in the world a sort of a benediction necessary for the

good of mankind. Once man was declared to be bad and the king full of

virtues, there was hardly any difficulty for political philosophy and religion

to recommend strict control of the people by the king.

There were thus monarchs both in the West and the East and in both

autocracy reigned supreme. Still in the West they could wrest a Magna

Carta from the king as early as in 1215 C.E. and produce t hink ers like

Hobbes, Eocke, Rousseau, Montesqueue and Bentham who helped change

the concept of kingship in course of time. But in the East, especially in

Islam, a rigid, narrow and limited scriptural education could, parrot-like,

repeat only one political theory-Man was nasty, brutish and short and must

be kept suppressed.

In the Siyasat Nama, Nizm-ul-Mulk Tusi stressed that since the kings

were divinely appointed, they must always keep the subjects in such a

position that they know their stations and never remove the ring of

servitude from their ears.- Alberuni, Fakhr-i-Mudabbir, Amir Khusrau,

Ziyauddin Barani and Shams Siraj Afif repeat the same idea.- As Fakhr-i-

Mudabbir puts it, if there were no kings, men would devour one

another.- Even the liberal Allama Abul Fazl could not think beyond this: If

royalty did not exist, the storm of strife would never subside, nor selfish

ambition disappear. Mankind (is) under the burden of lawlessness and lust-

The glitter of gems and gold in the Taj Mahal or the Peacock Throne, writes

Jadunath Sarkar, ought not to blind us to the fact that in Mughal India, man

was considered vile;-the mass of the people had no economic liberty, no

indefeasible right to justice or personal freedom, when their oppressor was

a noble or high official or landowner; political rights were not dreamt

of The Government was in effect despotism tempered by revolution or fear

of revolution.- Consequently, medieval Muslim political opinion could

recommend only repression of man and glorification of king.

The king was divinely ordained. Abul Fazl says that No dignity is higher

in the eyes of God than royalty Royalty is a light emanating from God, and

a ray from the sun, the illuminator of the universe.-

Kingship thus became the most general and permanent of institutions of

medieval Muslim world. In theory Islam claims to stand for equality of

men, in practice it encourages slavery among Muslims and imposes an

inferior status on non-Muslim. In theory Islam does not recognize Kingship;

in practice Muslims have been the greatest empire builders. Muhammadans

themselves were impressed with the concept of power and glamour

associated with monarchy. The idea of despotism, of concentration of

power, penetrated medieval mind with facility. Obedience to the ruler was

advocated as a religious duty. The ruler was to live and also enable people

to live according to the Quranic laws.- In public life, the Muslim monarch

was enjoined to discharge a host of civil, military and religious duties. The

Sultan was enjoined to do justice, to levy taxes according to the Islamic law,

and to appoint honest and efficient officers so that the laws of the Shariat

might be enforced through them.- At times, he was to enact Zawabits

(regulations) to suit particular situations, but while doing so, he could not

transgress the Shariat nor alter the Quranie law!- His military duties were to

defend Muslim territories, and to keep his army well equipped for eonquest

and extension of the territories of Islam.— The religious duty of a Muslim

monareh eonsisted in helping the indigent and those learned in the Islamie

law. He was to prohibit what was not permitted by the Shara. The duty of

propagating Islam and earrying on Jihad mainly devolved on him.— Jihad

was at onee an individual and a general religious duty.— Aecording to a

eontemporary A/im, if the Sultan was unable to extirpate infidelity, he must

at least keep the enemies of God and His Prophet dishonoured and

humiliated.— It must be said to his eredit that the Muslim Sultan, by and

large, worked according to these injunctions, and sometimes achieved

commendable success in his exertions in all these spheres.

As said earlier, there were autocratic monarchs both in the West and the

East. Still in the West there appeared a number of liberal political

philosophers who helped to change the concept of kingship in course of

time. But Muslims could not think on such lines, so that when in England

they executed their king after a long Civil War (1641-49), in India

Shahjahan, a contemporary of Charles I ruled as an autocrat in a golden age.

Even so autocracy took time to go even in Europe and there was no check

on the powers of the king in the Middle Ages, except for the institution of

feudalism.

Feudalism

Feudalism was a very prominent institution of the Middle Ages. It was

prevalent both in Europe as well as in India, although there were many

differences between the two systems. In Europe feudalism gathered strength

on the decline of the Western Roman Empire. After Charlemagne (800-814)

in particular, there was rapid decline in the monarchical power throughout

Europe, and governments failed to perform their primary duty of protecting

their peoples. The class of people who needed protection the most was the

petty landowner. In the earliest times the lands were free whether these

were held by ordinary freeman or a noble. In the absence of strong

monarchy, the possessor of the free land, threatened or oppressed by

powerful neighbours, sought refuge in submitting to some lord, and in the

case of a lord to some more powerful lord. In the bargain he surrendered his

land. For, when he begged for protection, the lord said: I can protect (only)

my own land. The poor man was thus forced to surrender the ownership of

his land to his powerful and rich neighbour, receiving it back in fief as a

vassal. (The word feudalism itself is derived from the French feodalite

meaning faithfulness). His children were left without any claim on that

land. He was also obliged to render service to his superior lord. In return he

was promised protection in his lifetime by his lord. The origins of feudalism

are thus to be traced to the necessity of the people seeking protection, and

exploitation by those who provided it.

Conditions were not the same everywhere, but the system was based on

contract or compact between lord and tenant, determining all rights and

obligations between the two. The vassal was obliged to render military

service, take his cases only to his own lord and submit to the decisions of

the lords court, and pay certain aids to the lord in times of need, like free

gifts or benevolences, aids at the marriage of the chiefs daughter, some tax

when the chief was in trouble or as ransom to redeem his person from

prison. These aids varied according to local customs and were often

extorted unreasonably.

On the other hand, for providing security to the vassal, it became

common for a chief or lord to have a retinue of bodyguards composed of

valiant youths who were furnished by the chief with arms and provisions

and who in turn devoted themselves to his service. These companions

received no pay except their arms, horses and provisions. With these

companions or troops the lords also conquered lands, and gave certain

portions of it to their attendants to enjoy for life. These estates were called

beneficia or fiefs, because they were only lent to their possessors, to revert

after death to their grantor, who immediately gave them to another of his

servants on the same terms. As the son commonly esteemed it his duty, or

was forced by necessity, to devote his arms to the lord in whose service his

father had lived, he usually received his fathers fief, or rather he was

invested with it anew. By the usage of centuries this custom became

hereditary. A fief rendered vacant by the death of the holder was taken

possession of by his son, on the sole condition of paying homage to the

feudal superior.

In the feudal system, therefore, the vassal and the lord benefited from one

another, although the latter mueh more, at the eost of the king. Junior

vassals could become powerful and rise in hierarchy to become sub-lords or

even great lords. They could have their own subordinate vassals in sub¬

infeudation. Kingly power, as always, continued to exist, but under

feudalism it was widely diffused. The privileges the lords enjoyed often

comprised the right of coining money, raising armies and waging private

wars, exemption from public tributes and freedom from legislative

control.— Sometimes the kings had to make virtue of necessity even to the

extent of granting titles and administrative fiefs to Counts etc. to be

administered by them. But the struggle between royalty and nobility (as in

England under William the Norman), continued. Of course, and ultimately,

it ended in the power of the lords sinking before that of the king.

In India feudalism did not usher in that spirit of civil liberty which

characterised the constitutional history of medieval England. Here the king

remained supreme whether among the Turks or the Mughals, and the

assignments of conquered lands were granted by him to lords, soldiers or

commoners or his own relatives as salary or reward in consideration of

distinguished military service in the form of iqtas or jagirsl^, sometimes

even on a hereditary basis, but they were not wrested from him. This system

was bureaucratic. There was also a parallel feudalistic organisation but the

possessor of land remained subservient to the king. It was based on personal

relationship. The vassals were given jagirs and assignments primarily

because of blood and kinship. On the other hand, the practice of permitting

vanquished princes to retain their kingdoms as vassals, or making allotment

of territories to brothers and relatives of the king, or giving assignments to

particular families of nobles, learned men and theologians as reward or

pension were feudalistic in nature. Some feudatories would raise their own

army, collect taxes and customary dues, pay tributes, and rally round the

standard of their overlord or king with their military contingents when

called upon to do so. But the assignee had no right of coining money. (In

fact, coining of money was considered as a signal of rebellion.) He

maintained his own troops but he had no right of waging private war.— He

could only increase his influence by entering into matrimonial alliances

with powerful neighbours or the royal family. In the Sultanate and the

Mughal empire the feudal system was more bureaucratic than feudalistic, in

fact it was bureaucratic throughout.— Here the feudal nobility was a

military aristoeraey whieh ineidentally owned land, rather than a landed

aristoeraey whieh oeeasionally had to defend Royal lands and property by

military means but at other times lived quietly.

But there were also many points of similarity between Indian and

European feudalism. In India Nazrana was offered to the lord or king when

an estate or jagir was bestowed upon the heir of the deeeased lord (Tika),

like the feudal relief in Europe. As in Europe, here too the praetiee of

eseheat was widely prevalent. Aids, gifts or benevolenees were eommon to

both. These consisted of offerings at the ascension of the king to the throne,

his weighment ceremony, on important festivals, eash and gifts at the

marriage of the chiefs daughter or son, gifts or a tax when the chief was in

trouble. In India the king always stood at the top of the regime. Feudal

institutions are apt to flourish in a state which lacks centralised

administration. The vastness of India makes it a veritable subcontinent, and

the rulers position was naturally different in each kingdom or region

aecording to local condition found there. But there was a eentral authority

too. The idea of a strong monareh was inseparable from Muslim psyehe and

Tureo-Mongol politieal theory. In India, under Muslim rule, great

importanee was attaehed to the saerosanet nature of the kings person. The

Indian system arose from eertain soeial and moral forees rather than from

sheer political necessity as in Europe, and that is why it survived throughout

the medieval period.

Whatever its merits and demerits, Indian feudalism reeognised division

of soeiety into people great and small, strong and weak, haves and have-

nots. Nobles were not equal to nobles; there were great Khans and petty

Amirs. Men were not equal to men; some were masters, others their slaves.

Women were not equal to men; they were subservient to men and

eonsidered to be their property. Perhaps the most prominent eharaeteristie

of the Medieval Age was the belief and acceptance of the 'fact' that men are

not born equal, or at least they could not be recognised as such.

Feudalism in Europe gradually disappeared with the coming of

Renaissance and Reformation, and formation of nation-states. In India

phenomena such as these did not occur. There was nothing like a

Renaissance in medieval India. There could be no reformation either,

because i nn ovation in religious matters is taboo in Islam. Some Muslim

monarchs were disillusioned with the state of religion and the power of the

Ulama (religious scholars).— Thai is why, probably, Alauddin Khalji (C.E.

1296-1316) contemplated founding a new religion,— Muhammad Tughlaq

(1325-51) was credited with similar intentions; and Akbar (1556-1605)

actually established the Din-i-Ilahi. Muslims feared that Alauddins new

religion must be quite different from the Muhammadan faith, and that its

enforcement would entail slaughter of a large number of Musalmans.— He

was dissuaded by his loyal counsellors from pursuing his project. All the

same it is significant that Alauddin Khalji and Jalaluddin Muhammad

Akbar did think of some sort of Reformation in Islam, but the former was

scared into abandoning the idea and the latter contented himself by just

organising a sort of brotherhood of like-minded thinkers.— Such

endeavours, strictly prohibited in Islam, could hardly affect India's Muslim

feudalistic society.

Europe in the middle ages too lived under a Roman Catholic imperium.

Its unity was theological, while its divisions were feudal. After Renaissance

the unity of the theological imperium was shattered and so were the old

divisions. European societies, after centuries of theological and territorial

wars, learnt to aggregate around a new category of the nation-state. In India

Muslim theological imperium never came to an end, nor persistent

resistance to it. Hence, the idea of a secular nation-state never found a

ground here.

Among other chief agencies that overthrew the feudal system were the

rise of cities, scouring of the oceans for Commercial Revolution and the

spread of knowledge, scientific knowledge in particular. In India there was

urbanisation under Muslim rule, but it has been grossly

exaggerated.— India had large urban centres before the arrival of Muslims.

Arab geographers become rapturous when describing the greatness of

Indias cities-both in extent and in demography-on the eve of Muslim

conquest and immigration.— During his sojourn in India Ibn Battuta visited

seventy-five cities, towns and ports.— Under Muslim rule many old cities

were given Muslim names. Thus Akbarabad (Agra), Islamabad (Mathura),

Shahjahanabad (Delhi) and Hyderabad (Golkunda) were not entirely new

built cities, but old populated plaees that were given new Islamie names,

mostly after the ruling kings. Giving new names to old eities was not an

extension of urbanisation as such, although it must be conceded that

Muslims loved city life and encouraged qasba like settlements.

Urbanisation in Europe gave impetus to industry and personal property and

founded a new set of power cluster-the middle class. The rise of this new

class, with its wealth and industrial importance, contributed more than

anything else to social and political development in Europe before which

the feudal relations of society almost gradually crumbled. The rise and

spread of this class in India and its impact on society remained min imal and

rather impereeptible. Edward Terry noted that it was not safe for merehants

and tradesmen in towns and eities, so to appear, lest they should be used as

filled sponges.— Moreland on the testimony of Bernier and others, arrives

at the eonelusion that in India the number of middle elass people was small

and they found it safe to wear the garb of indigenee.— Europe broke the

shaekles of feudalism by embarking upon Commereial Revolution and took

to the seas for the same. The Mughals in India fared miserably on water.

Even the great emperor Akbar had to purehase permission of the Portuguese

for his relatives to visit plaees of Islamie pilgrimage. Throughout medieval

India there was little ehange in the field of seientifle learning and thought.

Religious Wars

Eike feudalism, inter- and intra- religious wars too were a very prominent

feature of the medieval age. There were two great Semetie religions,

Judaism and Christianity, already in existenee when Islam was bom. Most

of the world religions like Vedie Hinduism (C. 2000-1500 B.C.), Judaism

(C. 1500 B.C.), Zoroastrianism (C. 1000 B.C.), Jainism and Buddhism (C.

600 B.C.), Confueianism (C. 500 B.C.) and Christianity had already eome

into being before Islam appeared on the seene in the seventh eentury. All

these religions, espeeially Hinduism, had evolved through its various

sehools a very highly developed philosophy. Jainism and Buddhism had

said almost the last word on ethics. So that not much was left for later

religions to contribute to religious philosophy and thought. So far as rituals

and mythology are concerned, these abounded in all religions and the

mythology of neighbouring Judaic and Christian creeds was freely

incorporated by Islam in its religion, so that Moses became Musa; Jesus,

Isa; Soloman, Sulaiman; Joseph, Yusuf; Jacob, Yaqub; Abraham, Ibrahim;

Mary, Mariam; and so on. But to assert its own identity, rules were made

suiting the requirements of Muslims imitating or forbidding Jewish and

Christian practices.—

Muhammad was born in Arabia in 569 and died in 632. In 622 he had to

migrate from Mecca to Medina (called hijrat) and this year forms the first

year of the Muslim calendar {Hijri). Islam got much of its mythology and

rituals from Judaism and Christianity, but instead of coming closer to them

it confronted them. From the very beginning Islam believed in aggression

as an instrument of expansion, and so spreading with the rapidity of an

electric current from its power-house in Mecca, it flashed into Syria, it

traversed the whole breadth of north Africa; and then, leaping the Straits of

Gibraltar it ran to the Gates of the Pyrenees.— Such unparalleled feats of

success were one day bound to be challenged by the vanquished. As a result

Christians and Muslims entered into a long-drawn struggle. The immediate

cause of the conflict was the capture of Jerusalem by the Seljuq Turks in

1070 and the defeat of the Byzantine forces at Manzikart in Asia Minor in

1071. For the next two centuries (1093-1291) the Christian nations fought

wars of religion or Crusades against Muslims for whom too these wars

meant the holy Jihad.

Christianity thus found a powerful rival in Islam because the aim of both

has been to convert the world to their systems. In competition, Islam had

certain advantages. If because of its late arrival, there was any problem

about obtaining followers, it was solved by the simple method of just

forcing the people to accept it. Starting from Arabia, Islam pushed its

religious and political frontiers through armed might. The chain of its early

military successes helped establish its credentials and authority. It was also

made more attractive than Christianity by polygamy, license of concubinage

and frenzied bigotry.— It sought outward expansion but developed no true

theory of peaceful co-existence. For example, it framed unlimited rules

about the treatment to be accorded to non-Muslims in an Islamic state, but

nowhere are there norms laid down about the behaviour of Muslims if they

happen to live as a minority in a non-Muslim majority state. Its tactic of

violence also proved to be its greatest weakness. In the course of Islamic

history, Muslims have been found to be as eager to fight among themselves

as against others.

The Crusades (so called because Christian warriors wore the sign of

cross), were carried on by European nations from the end of the eleventh

century till the latter half of the thirteenth century for the conquest of

Palestine. The antagonism of the Christian and Muhammadan nations had

been intensified by the possession of Holy Land by the Turks and their

treatment of the Christian pilgrims to Jerusalem. In these wars, the pious,

the adventurous, and the greedy flocked under the standards of both sides.

The first crusade was inspired by Peter the Hermit in 1093, and no less than

eight bloody wars were fought with great feats of adventure, heroism and

killings. In the last crusade the Sultan of Egypt captured Acre in 1291 and

put an end to the kingdom founded by the Crusaders. Despite their want of

success, the European nations by their joint enterprises became more

connected with each other and ultimately stamped out any Muslim

influence in Western Europe. But the most fruitful element in the crusades

was the entry of the West into the East. There was a constant conflict and

permanent contact between Christianity and Islam.

In this contact both sides lost and gained by turns, both culturally and

demographically, for both strove for expansion through arms and

proselytization. The successors of Saladin, who defeated the Christians in

the last crusade, were divided by dissensions. By the grace of those

disenssions the Latins survived. A new militant Muhammadanism arose

with the Mameluke Sultans of Egypt who seized the throne of Cairo in

1250. However, shortly afterwards there was a setback to Muslim power

when the Caliph of Baghdad was killed by the Mongols in 1258. On the

other hand, the prospect of a great mass conversion of the Mongols, which

would have linked a Christian Asia to a Christian Europe and reduced Islam

to a small faith, also dwindled and disappeared. The (Mongol) Khanates of

Persia turned to Muhammadanism in 1316; by the middle of the fourteenth

century Central Asia had gone the same way; in 1368-70 the native dynasty

of Mings was on the throne and closing China to foreigners; and the end

was a recession of Christianity and an extension of Islam which assumed all

the greater dimensions with the growth of the power of the Ottoman Turks

But a new hope dawned for the undefeated West; and this new hope was to

bring one of the greatest revolutions of history. If the land was shut, why

should Christianity not take to the sea? Why should it not navigate to the

East, take Muhammadanism in the rear, and as it were, win Jerusalem a

tergol This was the thought of the great navigators, who wore the cross on

their breasts and believed in all sincerity that they were labouring in the

cause of the recovery of the Holy Land, and if Columbus found the

Caribbean Islands instead of Cathay, at any rate we may say that

the Spaniards who entered into his labours won a continent for Christianity,

and that the West, in ways in which it had never dreamed, at last established

the balance in its favour.—

Crusades saved Western civilization in the Middle Ages. They saved it

from any self-centred localism; they gave it breadth-and a vision. On the

other hand, Muslim victories made Muslim vision narrow and myopic. So

that today Christians are larger in numbers and technologically and

militarily more advanced than Muhammadans. As these lines are being

written (August 1990), their armies and ships are spreading all over the

West Asian region beginning with Saudi Arabia.

To return to the medieval period. Religious wars between Christians and

Muhammadans alone did not account for killings on a large scale. The

Christians also fought bloody and long-drawn wars among themselves. The

Thirty Years War (1618-1648), for instance, decimated one-fifth population

of the region affected by it. Then there was the Inquisition. Inquisition was

a court or tribunal established by the Roman Catholic Church in the twelfth

century for the examination and punishment of heretics. England never

introduced it, Italy and France had only a taste of it. But in Spain it became

firmly established towards the end of the fifteenth century. It is computed

that there were in Spain above 20,000 officers of the Inquisition, called

familiars, who served as spies and informers. Imprisonment, often for life,

scourging, and the loss of property, were the punishments to which the

penitent was subjected. When sentence of death was pronounced against the

accused, burning the heretic in public was ordered as the church never

polluted herself with blood. The number of victims of the Spanish

Inquisition from 1481 to 1808 amounted to 341,021. Of these nearly 32,000

were burned at the stake.—

Islam outstripped Christianity in contributing to large-scale killings in

wars waged for religion or persecution of heretics. Each human being has

an idea or image of God in his mind. Consequently, there can be as many

Gods as there are human beings. Even according to one outstanding Sufi,

the paths by which its followers seek God are in number as the souls of

men.^ In view of this it is presumptuous to claim that there is only one God

or there are many Gods or there is no God at all. And yet in the name of

One God, and at that Merciful and Compassionate, what cruelties have not

been committed in the history of Islam? Arabia was converted during the

life-time of Muhammad. Immediately after the death of Muhammad, to

borrow the rhetoric of Edward Gibbon, in the ten years of the

administration of (Caliph) Omar (634-644) the Saracens reduced to his

obedience thirty-six thousand cities or castles, destroyed four thousand

churches or temples of the unbelievers, and edified fourteen hundred

moschs (mosques) for the exercise of the religion of Muhammad.— In these

unparalleled feats the number of the killed cannot be computed. Since many

pages in this book will be devoted to Muslim exertions in their endeavour to

spread Islam in India we may feel contented here to state that in this

scenario religion and religious wars became the very soul of thought, action

and oppression in the Middle Ages.

Censorship

Middle Ages is also known as Dark Ages. It is so called because there

were restrictions placed on the freedom of thought and any aberrations were

punished as heresy. Any idea away from the traditional was looked upon

with suspicion. New conceptions or knowledge gathered on the basis of

new experiments was taboo if it came into conflict with the Church or

contravened the Christian scriptures. This restriction on any new notions

made the period a dark age. But it required constant monitoring of peoples

thoughts and actions. The invention of printing and the rapid diffusion of

opinion by means of books, induced the governments in all western

countries to assume certain powers of supervision and regulation with

regard to printed matter. The popes were the first to institute a regular

censorship (1515) and inquisitors were required to examine all works

before they were printed. Only one example would suffice to illustrate the

position. Nicholas Copernicus was born in Poland in 1473: he taught

mathematics at Rome in 1500 and died in Germany in 1543. He researched

on the shape of the Earth, and concluded that the Sun was the centre round

which Earth and other planets revolved. In his De Orbium Celestium

Revolutionibus (On the Revolutions of the Celestial Orbs) he even

measured the diameter and circumference of the Earth fairly accurately. But

the Church believed the Earth to be flat, and the fear of Inquisition

discouraged Copernicus from publishing his outrageous researches till

about the close of his life, for the Church could do little harm to a man

about to die. Even so, his book was forbidden to the Roman Catholics for

long. The Inquisition freely used torture to extort confession; heretics were

broken on the wheel, or burnt at stake on cross-roads on Sundays for

punishment as well as an example for others.

In the medieval India under Muslim rule there was no printing press and

no research of the type done by Copernicus. The need for censorship arose

because Islam forbade any innovation in the thought and personal

behaviour of Muslims. Beware of novel affairs, said Muhammad, for surely

all innovation is error. What was not contained in the Quran or Hadis was

considered as innovation and discouraged. That is why Muslim learning in

India remained orthodox, repetitive and stereotyped. Free thought and

research in science and technology were ruled out. Fundamentalist writers

like Khwaja Baqi Billah (1563-1603), Shaikh Ahmad Sarhindi (1564-1624)

and Shah Waliullah (1702-1763) were considered as champion thinkers.

As Muslims must live in accordance with a set of rules and a code of

conduct, there was an official Censor of Public Morals and Religion called

Muhtasib. It was his duty to see that Muslims did not absent themselves

from public prayers, that no one was found drunk in public places, that

liquors or drugs were not sold openly. He possessed arbitrary power of

intervention and could enter the houses of wrong-doers to bring them to

book. Sir Alexander Burnes relates that he saw persons publicly scourged

because they had slept during prayer-time and smoked on Friday.— I. H.

Qureshi writes. It was soon discovered that people situated as the Muslims

were in India could not be allowed to grow lax in their ethical and spiritual

conduct without endangering the very existence of the Sultanate.—

Hurriedly converted, half-trained, Indian Muslims were prone to reverting

to their original faith which was full of freedom. Therefore, all the sultans

were very striet about enforeing Islamie behaviour on Muslims through the

ageney of Muhtasibs. Balban, Alauddin Khalji and Muhammad bin Tughlaq

were known for their severity in this regard. Muhammad bin Tughlaq

regarded wilful neglect of prayers a heinous crime and inflicted severe

chastisement on transgressors.— Women too were not spared; Firoz Shah

and Sikandar Lodi in particular forbade women from going on pilgrimage

to the tombs of saints.— The Department of Censor of Public Morals was

known as hisbah.—

Non-Muslims suffered even more because of censorial regulations.

Tradition divided them into seven kinds of offenders like unbelievers,

infidels, hypocrites, polytheists etc. who are destined to go to seven kinds of

hell from the mild Jahannum to the hottest region of hell called Hawiyah, a

bottomless pit of scorching fire. A strict watch was kept on their thought

and expression. They were to dress differently from the Muslims, they

could not worship their gods in public and they could not claim that their

religion was as good as Islam. A case which culminated in the execution of

a Brahmin may be quoted in some detail as an example.

A report was brought to the Sultan (Firoz Tughlaq 1351-88) that there

was in Delhi an old Brahman {Zunar dar) who persisted in publicly

performing the worship of idols in his house; and that the people of the city,

both Musalmans and Hindus, used to resort to his house to worship the idol.

This Brahman had constructed a wooden tablet (muhrak), which was

covered within and without with paintings of demons and other objects. On

days appointed, the infidels went to his house and worshipped the idol,

without the fact becoming known to the public officers. The Sultan was

informed that this Brahman had perverted Muhammadan women, and had

led them to become infidels. (These women were surely newly converted

and had not been able to completely cut themselves off from their original

faith). An order was accordingly given that the Brahman, with his tablet,

should be brought in the presence of the Sultan at Firozabad. The judges,

doctors, and elders and lawyers were summoned, and the case of the

Brahman was submitted for their opinion. Their reply was that the

provisions of the Law were clear: the Brahman must either become a

Musalman or be burned. The true faith was declared to the Brahman, and

the right course pointed out, but he refused to accept it. Orders were given

for raising a pile of faggots before the door of the darbar. The Brahman was

tied hand and foot and east into it; the tablet was thrown on the top and the

pile was lighted. The writer of this book (Shams Siraj Afif) was present at

the darbar and witnessed the execution the wood was dry, and the fire first

reached his feet, and drew from him a cry, but the flames quickly enveloped

his head and consumed him. Behold the Sultans strict adherence to law and

rectitude, how he would not deviate in the least from its decrees.—

The above detailed description gives the idea of burning at stake under

Muslim rule. Else similar cases of executions are many. During the reign of

Firoz himself the Hindu governor of Uchch was killed. He was falsely

accused of expressing affirmation in Islam and then recanting.— In the time

of Sikandar Lodi (1489-1517) a Brahman of Kaner in Sambhal was

similarly punished with death for committing the crime of declaring as

much as that Islam was true, but his own religion was also true.—

Astrology and Astronomy

Most medieval people of all creeds and countries believed in astrology.

Astrology literally means the science of the stars. The name was formerly

used as equivalent to astronomy, but later on became restricted in meaning

to the science or psuedo-science which claims to enable people to judge of

the effects and influences of the heavenly bodies on human and other

mundane affairs. Astrology was not to the medievals an unscientific

aberration. It was based on the understanding that the relationship of man to

the Universe is as the microcosm (the little world) is to the macrocosm (the

great world). Thus a knowledge of the heavens is essential for a true

understanding of man him self A knowledge of the movements of the

planets and their position in the heavens, would therefore be of the utmost

importance for man since, in the medieval phrase, superiors (in the heavens)

ruled inferiors (on earth): and not only man but all were subject to the

decrees of heavens, which themselves expressed the will of God.— Roger

Bacon (1214-1292?) considered astrology as the most practical of

sciences.—

Astrology was practised by Muslims as by all other medieval people.

Muhammad bin Qasim, the first invader of India, was despatched on his

mission only after astrologers had pronounced that the conquest of Sind

could be effected only by his hand.— Mahmud of Ghazni too believed in the

predictions of astrologers.— Timur the invader writes in his Malfuzat:

About this time there arose in my heart a desire to lead an expedition

against the infidels and become a ghazi, and felt encouraged when he

opened a fal (omen) in the Quran which said: O Prophet, make war upon

infidels and unbelievers and treat them with severity-and he launched his

attack on Hindustan.— The practice of consulting the Quran for fal was

common among medieval Muslims.— The savant Alberuni gives details of

Hindu literature on astrology and astronomy seen by him.— By and large

Muslim kings and commoners in India decided their actions on the advice

of the astrologers, soothsayers and omen mongers.

Peoples faith in astrology was reinforced for seeking solution to their

immediate problems and their curiosity to know their future. The first was

done by astrologers and palm-readers by examining the hand and face of

the applicant, turning over the leaves of the large book, and pretending to

make certain calculations and then decide upon the Sahet (saiet) or

propitious moment of commencing the business he may have in

hand.— Amulets and charms were also prescribed for warding off distress,

removing fear, obtaining success in an undertaking or victory in battle and a

hundred other similar problems.— The second was done by preparing a

horoscope. As usually practised, the whole heavens, visible and invisible,

was divided by great circles into twelve equal parts, called houses. The

houses had different names and different powers, the first being called the

house of life, the second the house of riches, the third of brethren, the sixth

of marriage, the eighth of death, and so on. To draw a persons horoscope, or

cast his nativity, was to find the position of the heavens at the instant of his

birth. The temperament of the individual was ascribed to the planet under

which he was born, as saturnine from Saturn,yovia/ from Jupiter, mercurial

from Mercury and so on. The virtues of herbs, gems, and medicines were

also supposed to be due to their ruling planets.

Kings and nobles gave large salaries to astrologers. The astrologers

prepared horoscopes of princes and the elite. Muslim kings got horoscopes

of all princes like Salim, Murad and Daniyal cast by Hindu Pandits.— Jotik

Ray, the court astrologer of emperor Jahangir used to make correct

predictions after reading the kings horoscope. He was once weighed against

gold and silver for reward.— There were men and women Rammals

(soothsayers) and clairvoyants at the court.— In short, the practice of

consulting astrologers was common with high and low. The people never

engaged even in the most trifling transaction without consulting them. They

read whatever is written in heaven; fix upon the Sahet, and solve every

doubt by opening the Koran.— No commanding officer is nominated, no

marriage takes place, and no journey is undertaken without consulting

Monsieur the Astrologer.— Naturally, the astrologers who frequented the

court of the grandees are considered by them eminent doctors, and become

wealthy.—

But there were charlatans also. They duped and exploited the poor and

the credulous. Besides some people then as now had no faith in astrology.

The French doctor Bernier was such an one. Describing the bazar held in

Delhi near the Red Fort, Francois Bernier (seventeenth century) says that

Hither, likewise, the astrologers resort, both Mahometan and Gentile. These

wise doctors remain seated in the sun, on a dusty piece of carpet, handling

some old mathematical instruments, and having open before them a large

book which represents the sign of the Zodiac. In this way they attract the

attention of the passenger by whom they are considered as so many

infallible oracles. They tell a poor person his fortune for a payssa Silly

women, wrapping themselves in a white cloth from head to foot, flock to

the astrologers, whisper to them all the transaction of their lives, and

disclose every secret with no more reserve than is practised by a penitent in

the presence of her confessor. The ignorant and infatuated people really

believe that the stars have an influence (on their lives) which the astrologers

can control.—

Astrology and astronomy are closely interlinked. In medieval times

astronomy was also considered a branch of psychology and medicine.

Astronomy has an undoubtedly high antiquity in India. The Arabs began to

make scientific astronomical observations about the middle of the eighth

century, and for 400 years they prosecuted the science of najum with

assiduity. The Muslims looked upon astronomy as the noblest and most

exalted of sciences, for the study of stars was an indispensable aid to

religious observances, determining for instance the month of Ramzan and

the hours of prayers. Halaku Khan (Buddhist) founded the great Margha

observatory at Azerbaijain. One at Jundishapur existed in Iran. In the

fifteenth century Ulugh Beg, grandson of Amir Timur (Tamerlane), built an

observatory at Samarqand. In Europe Copernicus in the fifteenth and

Galileo and Newton in the seventeenth century did valuable work in the

field of astronomy. In medieval India many Muslim chroniclers wrote about

the movements of planets and stars,— but the name of Sawai Jai Singh II of

Jaipur has become famous for his contribution to the science of astronomy.

He built observatories or Jantar-Mantars at many places in the country for

the study of the movements of stars and planets. A reputed geometer and

scholar, Sawai Jai Singh II built the Delhi Jantar-Mantar in C.E. 1710 at the

request of Mughal emperor Muhammad Shah. The observatory was used

for naked-eye sighting, continuously monitoring the position of the sun,

moon and planets in relation to background stars in the belt of the Zodiac.

His aim was basically to make accurate predictions of eclipses and position

of planets. He devised instruments of his own invention - the Samrat

Yantra, the Jai Prakash, and the Ram Yantra. The Misr Yantra was added

later by Jai Singhs son Madho Singh. The Samrat Yantra is an equinoctial

dial. The Yantra measures the time of the day, correct to half a second; and

the declination of the sun and other heavenly bodies. Other Jantar-Mantars

of Jai Singh were built at Ujjain, Mathura, Banaras and Jaipur.—

Alchemy, Magic, Miracles and Superstitions

Alchemy flourished chiefly in the medieval period, although how old it

might be is difficult to say. It paved the way for the modem science of

chemistry, as astrology did for astronomy. In the medieval age alchemy was

believed to be an exact science. But its aims were not scientific. It

concerned itself solely with indefinitely prolonging human life, and of

transmuting baser metals into gold and silver. It was cultivated among the

Arabians, and by them the pursuit was introduced into Europe. Raymond

Eully, or Eullius, a famous alchemist of the thirteenth and fourteenth

centuries, is said to have changed for king Edward I mass of 50,000 lbs. of

quicksilver into gold.— No such specific case is found in medieval India,

although there was firm belief in the magic or science of alchemy. A Sufi

politician of the thirteenth century, Sidi Maula by name, developed lot of

political clout in the time of Sultan Jalaluddin Khalji (1290-1296). He built

a large khanqah (hospice) where hundreds of people were fed by him every

day. He used to pay for what he bought by the queer way of telling the man

to take such and such amount from under such and such brick or coverlet,

and the tankahs (gold/silver coins) found there looked so bright as if they

had been brought from the min t that very moment.— He did not accept

anything from the people but spent so lavishly that they suspected him of

possessing the knowledge of Kimya va Simya (alchemy and natural

magic).—

The general solvent which at the same time was supposed to possess the

power of removing all the seeds of disease out of the human body and

renewing life, was called the philosophers stone. Naturally, there was a

keen desire to get hold of one. India was known for possessing knowledge

of herbs which prolonged life. Alberuni writes about the science of alchemy

{Rasayan) about which he so learnt in India: Its {Rasayans) principles

(certain operations, drugs and compound medicines, most of which are

taken from plants) restore the health and give back youth to fading old age

white hair becomes black again, the keenness of the senses is restored as

well as the capacity for juvenile agility, and even for co-habitation, and the

life of the people in this world is even extended to a long period.— In

Jamiul Hikayat Muhammad Ufi narrates that certain chiefs of Turkistan

sent ambassadors with letters to the kings of India on the following mission.

The chiefs said that they had been informed that in India drugs were

procurable which possessed the property of prolonging human life, by the

use of which the kings of India attained to a very great age. The Rais were

careful in the preservation of their health, and the chiefs of Turkistan

begged that some of this medicine might be sent to them, and also

information as to the method by which the Rais preserved their health so

long. The ambassadors having reached Hindustan, delivered the letters

entrusted to them. The Rai of Hind having read them, ordered the

ambassadors to be taken to the top of an excessively lofty mountain

(Himalayas?) to obtain it. In the same book a story refers to a chief of

Jalandhar, who had attained to the age of 250 years. In a note Elliot

comments that this was a favourite persuasion of the Orientals.— But

Alberunis conclusion is crisp and correct. He writes: The Hindus do not pay

particular attention to alchemy, but no nation is entirely free from it, and

one nation has more bias for it than another, which must not be construed as

proving intelligence or ignorance; for we find that many intelligent people

are entirely given to alchemy, whilst ignorant people ridicule the art and its

adepts.—

Belief in magic too was a universal weakness of the middle ages. The

invocation of spirits is an important part of Musalman magic, and this

{dawat) is used for the following purposes: to command the presence of the

Jinn and demons who, when it is required of them, cause anything to take

place; to establish friendship or enmity between two persons; to cause the

death of an enemy; to increase wealth or salary; to gain income gratuitously

or mysteriously; to secure the accomplishment of wishes, temporal or

spiritual.— So, magic was practised both for good purposes and evil

intentions, for finding lucky days for travelling, catching thieves and

removing diseases as well as inflicting diseases on others. The first was

called spiritual {Ilm-i-Ruhani) and the latter Shaitani Jadu. Although Islam

directs Musalmans to believe not in magic— yet the belief was

universal.— It involved visit to tombs, use of collyrium or pan (betel), and

all kinds of antics and ceremonials for desiring death for others and success

for self There were trained magicians (Sayana).— They fleeced the fools,

both rich and poor, to their hearts content. A highly popular book on magic

among the Muslims in the medieval period was Jawahir-i-Khamsa by

Muhammad Ghaus Gauleri.—

Belief in magic and sorcery and worship of saints living and dead was

linked with belief in miracles and superstition. The argument was that the

elders and saints helped when they were alive, they could still help when

dead and so their graves were worshipped. There was belief in miracles for

the same reason. An evil eye could inflict disease and there was fear of

witchcraft. A blessing could cure it and so there was faith in the miraculous

powers of saints. In medieval times physicians were few, charlatans many,

and even witch doctors flourished. Amir Khusrau mentions some of the

powers of sorcery and enchantment possessed by the inhabitants of India.

First of all they can bring a dead man to life. If a man has been bitten by a

snake and is rendered speechless, they can resuscitate him even after six

months.—

There is nothing surprising about the belief in miracles by medieval

Muslims, in particular about their Sufi Mashaikfi. In theory Islam

disapproved of miracles. In practice it became a criterion by which Sufi

Shaikhs were Judged and the common reason why people reposed faith in

them. Many Sufi Shaikhs and Faqirs were considered to be Wali who could

perform karamat or miracles and even istidraj or magic and

hypnotism.— Shaikh Nizamuddin Auliya held that it was improper for a

Sufi to show his karamat even if he possessed supernatural powers.— But

belief in alchemy and miracles was common even among Sufi Mashaikh—

and there are dozens of hagiological works and biographies of Sufi saints

containing stories of such miracles including Favaid-al-Fuad, Siyar-ul-

Auliya and Khair-ul-Majalis which are considered by many Muslims to be

pretty authentic. There are unbelievable stories, hardly worth reproducing.

It is difficult to say when the stories of the karamat of the Sufi saints began

to be told. But they helped the Sufis take Islam to the masses. It is believed

that impressed by these stories or actual performance of miracles, many

Hindus became their disciples and ultimately converted to Islam.

Belief in ghosts of both sexes was widespread. Nights were frightfully

dark. Right upto the time of Babur there were no candles, no torches, not a

candle-stick.— Even in the Mughal palace utmost economy was practised in

the use of oil for lighting purposes.— The common man lived in utter

darkness after nightfall. And ghosts, goblins and imaginary figures used to

haunt him. Sorcerers and witch doctors tried to help men and particularly

women who were supposed to have been possessed by ghosts.

Education

Belief in astrology and alchemy, magic and witchcraft, miracles and

superstition was there both in the West and the East in the middle ages.

Europe released itself from mental darkness sooner because of spread of

education and early establishment of a number of universities. Oxford was

set up in the twelfth century, Cambridge in 1209. Paris University came into

being in the twelfth. Angers in the thirteenth and Orleans in 1231. In Italy,

Salerno was founded in the tenth century, Arezzo in 1215, Padua

1222, Naples 1224, Siena 1246, Piacenza 1248, Rome 1303, and Pisa 1343.

Such was the situation throughout Europe.— The emergence of universities

in such large numbers, with still larger number of sehools whose seleeted

pupils went to the universities, led to a spurt in learning whieh may explain

the birth and flowering of Renaissance in Italy and Reformation in

Germany. Martin Luther, who created a revolution in religion, was a student

at the University of Erfurt founded in 1343.

In the early years of Islam the Muslims eoneentrated mainly on

translating and adopting Creek seholarship. Aristotle was their favourite

philosopher. Scientific and mathematical knowledge they adopted from the

Greeks and Hindus. This was the period when the Arabs imbibed as much

knowledge from the West and the East as possible. In the West they learnt

from Plato and Aristotle and in India Arab scholars sat at the feet of

Buddhist monks and Brahman Pandits to learn philosophy, astronomy,

mathematies, medicine, chemistry and other subjects. Caliph Mansurs (754-

76) zeal for learning attracted many Hindu scholars to the Abbasid court. A

deputation of Sindhi representatives in 771 C.E. presented many treatises to

the Caliph and the Brahma Siddhanta of Brahmagupta and his Khanda-

Khadyaka, works on the seienee of astronomy, were translated by Ibrahim

al-Fazari into Arabie with the help of Indian seholars in Baghdad. The

Barmak (originally Buddhist Pramukh) family of ministers who had been

eonverted to Islam and served under the Khilafat of Harun-ur-Rashid (786-

808 C.E.) sent Muslim seholars to India and weleomed Hindu seholars to

Baghdad. Onee when Caliph Harun-ur-Rashid suffered from a serious

disease which baffled his physicians, he called for an Indian physician,

Manka (Manikya), who cured him. Manka settled at Baghdad, was attached

to the hospital of the Barmaks, and translated several books from Sanskrit

into Persian and Arabic. Many Indian physicians like Ibn Dhan and Salih,

reputed to be descendants of Dhanapti and Bhola respectively, were

superintendents of hospitals at Baghdad. Indian medical works of Charak,

Sushruta, the Ashtangahrdaya, the Nidana, the Siddhayoga, and other

works on diseases of women, poisons and their antidotes, drugs,

intoxieants, nervous diseases ete. were translated into Pahlavi and Arabie

during the Abbasid Caliphate. Sueh works helped the Muslims in extending

their knowledge about numerals and medieine.— Havell goes even as far as

to say that it was India, not Greeee, that taught Islam in the impressionable

years of its youth, formed its philosophy and esoterie religious ideals, and

inspired its most eharaeteristie expression in literature, art and

architecture.— Avicenna (Ibn Sina) was a Persian Muslim who lived in the

early eleventh century and is known for his great canon of medicine.

Averroes (Ibn Rushd), the jurist, physician and philosopher was a Spanish

Muslim who lived in the twelfth Century. A1 Khwarizmi (ninth century)

developed the Hindu nine numbers and the zero (hindisa). A1 Kindi (ninth

century) wrote on physics, meteorology and optics. A1 Hazen (A1 Hatim C.

965-1039) wrote extensively on optics and the manner in which the human

eye is able to perceive objects. Their best known geographers were A1

Masudi, a globe-trotter who finished his works in 956 and the renowned A1

Idrisi (1101-1154). Although there is little that is peculiarly Islamic in the

contributions which Occidental and Oriental Muslims have made to

European culture,— even this endeavour had ceased by the time Muslim

rule was established in India. In the words of Easton, when the barbarous

Turks entered into the Muslim heritage, after it had been in decay for

centuries, did Islam destroy more than it created or preserved.— For

instance, Ibn Sina had died in Hamadan in 1037 and in 1150 the Caliph at

Baghdad was committing to the flames a philosophical library, and among

its contents the writings of Ibn Sina him self In days such as these the

Eatins of the East were hardly likely to become scholars of the

Muhammadans nor were they stimulated by the novelty of their

surroundings to any original production.—

Similar was the record of the Turks in India. No universities were

established by Muslims in medieval India. They only destroyed the existing

ones at Sarnath, Vaishali, Odantapuri, Nalanda, Vikramshila etc. to which

thousands of scholars from all over India and Asia used to seek admission.

Thus, with the coming of Muslims, India ceased to be a centre of higher

Hindu and Buddhist learning for Asians. The Muslims did not set up even

Muslim institutions of higher learning. Their maktabs and madrasas catered

just for repetitive, conservative and orthodox schooling. There was little

original thinking, little growth of knowledge as such. Education in Muslim

India remained a private affair. Writers and scholars, teachers and artists

generally remained under the direct employment of kings and nobles. There

is little that can be called popular literature, folk-literature, epic etc. in

contemporary Muslim writings. The life of the vast majority of common

people was stereotyped and unrefined and represented a very low state of

mental culture.—

Tenor of Life

The chief amusement of the nobles of the ruling class was warfare. In

this they took delight that was never altogether assuaged. If they could not

indulge in this, then, in later ages, they made mock fights called jousts or

tournaments. If they could not always fight men, they hunted a nim als.

Every noble learned to hunt, not for food-though this was important too-but

for pleasure. They developed the art of hunting birds as well as taming and

flying birds.— Some nobles were learned, humble, polite and courteous-

hut such were exceptions rather than the rule. Since there was little

academic activity, most of the elite passed their time in field sports,

swordsmanship and military exercises. Their coat of mail was heavy and

cumbersome; a fall from horse was very painful and sometimes even fatal.

Such a situation was common both in Europe and India. But in Europe the

medieval age was an age of chivalry. It tended to raise the ideal of

womanhood if not the status of women. Chivalrous duels and combats were

generally not to be seen among Muslims in India. Such artificial

sentimentality has nothing in common with (their) warrior creed.—

The medieval age, by and large, conjures up vision of times in which

everything was backward. Eife was nasty, brutish and short. The ruler and

the ruling classes were unduly cruel. Take the case of hunting animals and

birds. In the process fields with standing crops were crushed and destroyed,

often wantonly. The common man suffered. Man wallowed in ignorance.

Man was dirty, there was no soap, no safety razor. Potable water was

provided by rivers, else it was well-water or rainwater collected in tanks,

ponds and ditches. Political and religious tyranny, the institution of slavery,

polygamy and inquisition or hisbah rendered life unpalatable. Men had few

rights, women fewer. Wife was a possession; parda was a denial of the

dignity of woman as woman. Medicine was limited, treatment a private

affair, medicare was no concern of the state. Police was nowhere to be seen

for seeming redressal of grievances while sorcery and magic, and ghosts

and goblins were ever present to frighten and harm. Means of transport and

communication were primitive. Most people hardly ever moved out of their

villages or towns. Society was closed as was the mind.

But there was no scarcity of daily necessities of life. True, in medieval

India there was no tea, no bed-tea. Coffee came late. It is mentioned by

Jahangir in his memoirs.— Tomato or potato did not arrive before the

sixteenth century. Still, there was no dearth of palatable dishes for the

medieval people to eat. Wheat and rice were common staples.— Rice is said

to be of as many kinds as twenty-one.— Paratha, halwa and harisa, were

commonly eaten by the rich,— Khichri and Sattu by the poor.— Muslims

were generally meat-eaters and mostly ate the flesh of cow and goat though

they have many sheep, because they have become accustomed to

it.— Fowls, pigeons and other birds were sold very cheap.— Vegetables

mentioned in medieval works are pumpkin, brinjal, cucumber, jackfruit

{kathal), bitter gourd (karela), turnip, carrot, asparagus, various kinds of

leafy vegetables, ginger, garden beet, onion, garlic, fennal and thyme.— Dal

and vegetables were cooked in ghee, tamarind was commonly used, and

pickles prepared from green mangoes as well as ginger and chillies were

favourites.— There were fresh fruits, dry fruits and sweets. Apples, grapes,

pears and pomegranates— were for important people. Melons, green and

yellow {kharbuza and tarbuz), were grown in abundance.— Orange, citron

{utrurj), lemon {limun), lime (lim), jamun, khirni, dates and figs were in

common use as also the plantains.— Sugar-cane was grown in abundance

and Ziyauddin Barani, writing in Persian, gives its Hindustani name ponder.

Mango, then as now, was the most favourite fruit of India.— Sweet-meats

were of many kinds, as many as sixty five.— Some names like reori, sugar-

candy, halwa and samosa are familiar to this day. Ibn Battutas description of

the preparation of samosa would make ones mouth water even

today: Minced meat cooked with almond, walnut, pistachios, onion and

spices placed inside a thin bread and fried in ghee.— Wine and other

intoxicants like hemp and opium, though prohibited in Islam, were freely

taken by those who had a liking for it.— Betel (then known by its Sanskrit

name tambul) was an after dinner delicacy.—

Muslim elite were very fond of eating rich and fatty food, both in quality

and quantity. Their gluttony was whipped up as much by the love of

sumptous dishes as by their habit of hospitality. It also received stimulus

from the use of drinks and drugs and was best exhibited during excursions,

picnics and arranged dinners. According to Sir Thomas Roe, twenty dishes

at a time were served at the tables of the nobles, but sometimes the number

went even beyond fifty. But for the extremely poor, people in general

enjoyed magnificent meals with sweetmeats and dry and fresh fruit

added.— All this was possible because food grains were extremely cheap

throughout the medieval period as vouched by Barani for the thirteenth,

Afif for the fourteenth, Abdullah for the fifteenth and Abul Fazl for the

sixteenth centuries.— The poor benefited by the situation but the benefit

was probably offset by the force and coercion used in keeping prices low as

asserted by Barani and Abdullah, the author of Tarikh-i-Daudi.

In matters of clothing also, India was better placed than many other

countries in the middle ages. The textile industry of India was world-

famous. The Sultan, the nobles and all the rich dressed exceedingly well.—

The costly royal robes, the gilded and studded swords and daggers, the

parasols {chhatra) of various colours were all typically Indian paraphernalia

of royal pomp and splendour. The use of rings, necklaces, ear-rings and

other ornaments by men was also due to Indian wealth and opulence. The

dress of the Sultan and the elite consisted of kulah or head-dress, a tunic

worked in brocade and long drawers. The habit of dyeing the beard was

common. It added in the old a zest for life as did the slanting of cap in the

young. The Hindu aristocracy dressed like the Muslim

aristocracy,— except that in place of kulah they used a turban, and in place

of long drawers they wore dhoti trimmed with gold lace. The Muslims

dressed heavily but the Hindus were scantily dressed. They cannot wear

more clothing on account of the great heat, says Nicolo Conti.— The

orthodox Muslims wore clothes made of simple material like linen. The

dress worn by scholars at the Firoz Shahi Madrasa consisted of the Syrian

jubbah and the Egyptian dastar.^ But there was no special uniform for

any one, not even for soldiers. In the villages the poor put on only a loin¬

cloth {langota) which Babur takes pains to describe in detail.—

Muslim women dressed elaborately and elegantly. The inmates of the

harems of the kings and nobles, indeed even their maids and servants

dressed in good quality clothes.— Lehanga, angia and dupatta were the

common set for women as seen in medieval miniatures. They wore shoes

made of leather and silk, often ornamented with gold thread and studded

with precious stones. Besides women all over the country wore all kinds of

ornaments, the rich of gold and silver, pearls and precious stones, the poor

of silver and beads. Care of the teeth, painting the eyes, use of antimony,

lampblack, henna, perfumed powders, sandal-wood, aloes-wood, otto of

roses and wearing of flowers added elegance to personality and beauty to

life.—

Cities in medieval India were few, but they were large and impressive.

Foreign visitors like Athnasius Nikitin and Barbosa give a favourable

comparison of Indian cities with those of Europe. Cities and towns

generally were built on the pattern of the metropolis of Delhi. Shihabuddin

Ahmad, the author of Masalik-ul-Absar (fourteenth century), writes: The

houses of Delhi are built of stone and brick The houses are not built more

than two storeys high, and often are made of only one.— Besides, there

must have been hut-like houses of the poor huddled together in congested

localities. In the Delhi of the medieval period there was the fort and palace

of the Sultan, cantonment area of the troops, quarters for the ministers, the

secretaries, the Qazis, Shaikhs and faqirs. In every quarter there were to be

found public baths, flour mills, ovens and workmen of all professions.— In

the villages, the peasants lived in penury. But if there was little to spare,

there was enough to live by.— There were indoor and outdoor games for all

to play-chess,— backgammon, pachisi, chausar, dice, cards, kite-flying,

pigeon-flying, polo, athletics; cock, quail and partridge fighting; and

childrens games.— Public entertainments, as on the occasion of marriage in

the royal family, comprised triumphal arches, dancing, singing, music,

illuminations, rope-dancing and jugglery. The juggler swallowed a sword

like water, drinking it as a thirsty man would sherbet. He also thrust a kni fe

up his nostril. He mounted little wooden horses and rode upon the air Those

who changed their own appearance practised all kinds of deceit. Sometimes

they transformed themselves into angels, sometimes into demons.—

Conclusion

There were certain characteristics of the medieval age which have

survived to this day among the Muslims. These give an impression that

Muslims are still living in medieval times. Therefore, the legacy of the

medieval age is medievalism, especially among the Muslims. The days of

autocracy, feudalism and religious wars are over, but not so in many Islamic

countries. While Christians in the West are beeoming modem and seeular,

the same eannot be said about Muhammadans. In the field of edueation, the

Printing Press in Europe became a potential medium of developing and

spreading knowledge. Medieval Indian Muslims were not interested in this

development, but even now the teaehing in maktabs and madrasas is no

different from what it used to be in the medieval period. In religious matters

freedom of expression and critieal analysis is still suppressed as was done

in the medieval age. As for example, the translator of the Japanese edition

of Salman Rushdies controversial novel. The Satanic Verses, Professor

Hitoshi Igarashi, was found murdered in his University Campus on 12 July

1991. Mr. Gianni Palma, the Italian publisher of its translation, was attaeked

by an angry Muslim during a news eonferenee in February 1990. And

Salman Rushdie himself lives in hiding in perpetual seare of assassination

beeause of the Fatwa. The Islamie Government of Pakistan has deeided to

make death by hanging mandatory for anyone who defames Prophet

Muhammad. Previously, a person eonvieted of blasphemy had a ehoiee of

hanging or life imprisonment.— No wonder a Muslim like Raflq Zakaria

eould write about Muhammad in the only way he did though many ehapters

of this book fail to earry eonvietion beeause they are too defensive and

apologetie.— On the other hand many innoeuous books eoneerning

medieval studies or Islam have been banned in India in deferenee to the

wishes of Muslim fundamentalists. Even now Muslim festivals and

auspieious days are declared so, as was done in medieval times, after

aetually sighting the new moon, despite the strides made in the field of

Astronomy which tell years in advance when the new moon would appear.

In the soeial sphere, Muslim women are still made to live in parda, and

polygamy is practised as a matter of personal law if not as a matter of

religious duty. In the political field, Muslim rule in medieval India was

based on the doetrines of Islam in which discrimination against non-

Muslims was central to the faith. Even today Hindu shrines are broken not

only in Pakistan and Bangladesh but even in Kashmir as a routine matter.

It would normally be expected that historical writing on Muslim rule in

medieval India would tell the tale of this discrimination and the sufferings

of the people, their foreed conversions, destruction of their temples,

enslavement of their women and ehildren, eandidly and repeatedly

mentioned by medieval Muslim ehronielers themselves. But euriously

enough, in place of bringing such facts to light there is a tendency to gloss

over them or even suppress them. Countries which in the middle ages

completely converted to Islam and lost links with their original religion and

culture, write with a sense of pride about their history as viewed by their

Islamic conquerors. But India's is a different story. India could not be

Islamized and it did not lose its past cultural anchorage. Naturally, it does

not share the sense of glory felt by medieval Muslim chroniclers. But some

modern secularist writers do praise Muslim rule in glowing terms. All

historians are not so brazen or such distortionists. Hence the history of

Muslim rule in India is seen through many coloured glasses. It is necessary,

therefore, to take a look at the schools or groups of modem historians

writing on the history of medieval India so that a balanced appraisal of the

legacy of Muslim mle in India may be made.

Footnotes:

- Cited in Bosworth, The Ghaznavids, p. 49.

- Albemni II, p. 161. Also Barani, Fatawa-i-Jahandari.

- Fakhr-i-Mudabbir, Tarikh-i-Fakhruddin Mubarak Shah, p. 13.

-Ain, I, p. 2.

- Sarkar, A Short History of Aurangzeb, p.464.

-Ain, I, pp. 2-3, 6.

- Barani, pp. 293-94.

- Barani, p. 64.

- Barani, Fatawa-i-Jahandari, p. 73. Also Tripathi, Some Aspects of

Muslim Administration, p. 5.

- Adab-ul-Harb, fols. 132b-133a.

— Ibid, fols.56b; Barani, p.73;Adab-ul-Harb, fols.8b-10c.

— Hasan Nizami, Tajul Maasir, trs.by S.H. Askari, Patna University